World War Two

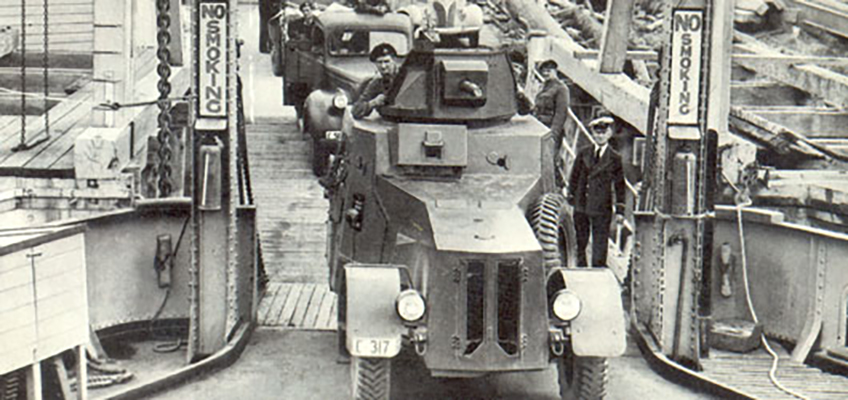

The army crossing at Peats Ferry during World War Two.

The army crossing at Peats Ferry during World War Two.

During the darkest days of World War Two, as Australia braced for invasion, Hornsby Shire prepared itself for frontline fighting.

When war against Nazi Germany broke out in September 1939 Hornsby Shire did its part, sending many people to join the fight while those at home raised funds through the Shire of Hornsby Patriotic and War Fund. The Hornsby RSL kept troops up to date with the Home Front News, which ran from March 1941 until October 1945 and eventually had a print run of 1600, and Hornsby Shire Council set up the Hornsby Shire Salvage Fund to coordinate the collection of recyclable materials for the war effort.

Then on 7 December 1941 Japan attacked Pearl Harbor. Suddenly the war was much closer to home and not going at all well. By February 1942 Japan had captured Singapore and launched the first air raid on Darwin.

Hornsby Shire is Sydney’s northern gateway and guardian of the strategic Hawkesbury River, so it was central to the Government’s plans to repel an invasion. The importance of the Hawkesbury River Railway Bridge was highlighted after maps salvaged from one of the Japanese midget submarines that raided Sydney Harbour in 1942 showed the bridge outlined in red. The railway bridge was protected from attack by two anti-submarine nets that stretched from Brooklyn to Dangar Island and Dangar Island to Little Wobby, as well as anti-aircraft guns that were positioned at various points around the bridge.

Meanwhile, a convict-built sandstone bridge in Muogamarra Nature Reserve was demolished and signs identifying suburbs were removed to confuse the enemy. There was also preparation for the destruction of local livestock and crops or their evacuation to inland areas in the event of an invasion.

To make the Hawkesbury more impassable, the Naval Control Board decided to impound small boats. In Operation Berowra Boat Guard around 2000 boats were gathered at Crosslands. The task of keeping them out of Japanese hands was made far easier in April 1942 when a flash flood destroyed many of them as they were being stacked on the river flats.

It is believed this was when the 19th Century cannon that stood outside the Council Chambers was buried, presumably to prevent it falling into Japanese hands. The cannon was forgotten until it was unearthed by construction workers in 1970.

Though there were no air raids on Sydney, blackouts were practiced and “brown-out shields” were placed on all street lights. These were removed in September except from lights that could be seen from sea, though Berowra’s street lights were not back in operation until 1944. There were air raid sirens located at strategic points, such as Hornsby Park and Asquith Railway Station, and there were regular air raid drills. All schools were provided with trenches – Hornsby Public School’s was where the swimming pool now is.

The Federal Government set up the National Emergency Service, similar to Britain’s “Dad’s Army”. Shire President Charles Somerville was made Chief Warden of Hornsby Shire, with 2000 personnel at his command. The Shire was split into divisions, which were divided into warden’s posts that were commanded by senior wardens. The 38 warden’s posts in Hornsby Shire were manned 24 hours a day, though often this was by the warden’s wife while he was at work. The wardens compiled household registers, recording residents and their skills, telephones, motor vehicles, tools and air raid shelters. The NES also had first aid posts, such as the one stationed in Hornsby Girls High School gymnasium. Hornsby Shire Council purchased ambulances for the NES.

The fear that Japan would fire-bomb the local bushland spurred the formation of the Hornsby Shire Volunteer Bush Fire Brigade which was coordinated by the NES.

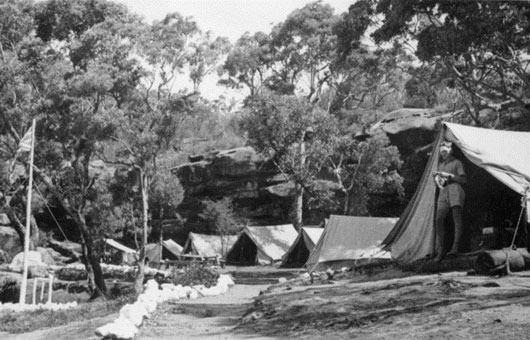

Hornsby Shire acted as a training ground for Australian troops. The Army used the old Thornleigh quarry as a shooting gallery and the crew of the Krait trained in Cowan Creek before their daring commando raid on Singapore Harbour in September 1943.

Amid all the destruction, the war saw the building of vital local infrastructure. While Australia hoped to make the Hawkesbury River a barrier against invaders if they came, in the meantime its own troops and supplies needed to cross regularly. Motor vehicles had to cross by ferry until 1945, when the opening of the Pacific Highway’s bridge alleviated a major transport bottleneck.

As if the lack of a road bridge wasn’t bad enough, the original railway bridge had to be decommissioned due to deterioration of the piers. As the war progressed the need for a replacement became acute. The defensive mining of coastal waters made shipping difficult and most passengers and freight went north from Sydney by rail. The weakness in the old bridge necessitated a speed limit of five miles an hour that created another bottleneck. Construction of a second bridge began in 1939 and was completed in 1946.

On 15 August 1945 Japan surrendered and on 23 August Hornsby Shire Council passed a motion:

“That Council place on record its thankfulness that the victorious peace so long awaited has now eventuated, its gratitude to the men and women of the Services for their selfless devotion to duty and their share in the successful conduct of the War, its sincere thanks to the personnel of the various organisations at home for their untiring efforts, and its appreciation of the patient consideration and understanding and forbearance of the residents of the Shire during the difficult years of War.”